By Owen Louis David

It’s simple: if you are going to build a million-person city on Mars (as Space X plan), you are going to have to grow food. Importing all that food from Earth would imply bringing in something like 1.5 million tons per Earth Annum, which would require 15,000 Starship flights costing tens or hundreds of billions of dollars. Beyond the first decade of Mars colonisation, food importation is not an option. In-situ agriculture is the only game in town.

So we know what we need to do. But how are we going to grow food on a planet with an atmosphere that’s hardly there and with so many other physical challenges to creating a successful agricultural sector?

Well, thankfully, we know a lot more about growing food in such circumstances than we did over 70 years ago. Since the dawn of the space age, there have been huge advances on many fronts that mean growing food on Mars, while not exactly a walk in the park, will be well within the realm of the possible. The sorts of technologies we can now draw on include photovoltaic power (solar panels, working with vastly improved battery storage), polytunnel farming, efficient water recycling, robotics (including robot harvesting), dwarf crops, hydroponic farming, controlled environment agriculture (CAE), artificial meat, artificial dairy farming, computerised monitoring, and advanced aerogel materials (useful for heat insulation). When we bring these technologies together, we have the makings of successful farming on Mars.

So what are the key issues for farming on Mars?

Well the answer to that has to be that these issues are going to vary over time. There will be a huge difference between the conditions existing during the first few missions and during the time of terraformation. We also need to differentiate between different types of farming we know from Earth: arable farming, orchard farming of fruit and nuts, and dairy and livestock farming. Some will likely continue in familiar ways. Others may follow divergent paths.

One key issue already mentioned is that the atmosphere is much, much thinner on Mars than on Earth. Many Mars-watchers will know this but in case you aren’t up to speed on this topic, you should know the average atmospheric density on Mars is only 0.06% of Earth’s. So, even though plants love carbon dioxide and the Mars atmosphere is 96% CO2, plants can’t survive outdoors on Mars as things stand because of that extremely thin atmosphere and, even more so, when you factor in the generally freezing temperatures on Mars.

Although Mars, particularly in the equatorial regions, can enjoy balmy summer days when the air temperature reaches as high as 30 degrees Celsius, that is very much the exception. Normally, when it comes to the Mars climate, we are talking “deep mid-winter in Siberia” for most of the Mars year (which, incidentally, is nearly as long as two Earth years).

Credit: Wickes Farms Strawberries

Plants on Earth usually require nutrient-rich soil to grow in, water to keep them hydrated, air to breathe, access to sufficient solar radiation and a reasonable temperature range. So how can we meet those requirements on Mars prior to terraformation? Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Soil: Mars has a surface regolith that often resembles Earth-based soils (clay, sand and gravel), depending on location. That’s a good start. But in terms of nutrient value, Mars’s soil is very poor and would require some help to make it a good growing medium. Early on, it will be easy enough to import nutrient solutions from Earth to help condition the soil. However, as the population grows, Mars will have to find its own answers. Obviously human faeces, food waste, and crop waste can be processed to create a good compost for crops. This regenerative agriculture approach can be applied crop by crop. It is likely though that soil manufacturing facilities will need to be developed to ensure that the right nutrients are integrated into soil. These facilities would eventually be producing millions of tons of nutrient-rich soil every year. We would see processes such as rock-grinding, soil mixing (bringing together different types of soil medium), and nutrient integration, so enabling the production of optimal soil for different crops. Mars is not as blessed with easily accessible nitrogen as we see on Earth and, so, chemical processing industries extracting nitrogen from available minerals will be very important. We might also see early attempts to import nitrogen from the asteroid belt.

We should also also ask to what extent we really need soil per se on Mars. There are alternative methods of producing healthy crops including hydroponic and aeroponic farming where you use water or an aerosol spray to deliver nutrients to the plant’s root system. However, the evidence seems to be that crops like wheat will be more successfully grown in soil.

Water: The Red Planet has plenty of water (though it is nearly all in the form of water ice which would need to be melted before use). Obviously, water would have to pass through a filtration process to ensure it was safe for agricultural use (essentially meaning it would be the equivalent of potable water). So, although Mars has no rainfall we can pretty much tick the box for water.

Air: Given its very high CO2 content, Mars’s air is well suited to agriculture, as far as plant growth goes. Essentially it needs to be concentrated (using air intake systems) and brought up to at least around 20% of Earth’s atmospheric density. At that density, there will be more than enough CO2 in the air for crops to grow optimally. It is likely that farm areas within the colony will be isolated from general residential areas in order that indoor farming can take place in a low pressure, high CO2 environment. Workers needing to enter the farm environment (probably infrequently, given the robotic input to agriculture on Mars) will therefore need to wear breathing apparatus. It probably makes sense to isolate farm areas from residential areas in any case to prevent microbes migrating to areas of human habitation where they might be a health threat.

Access to solar radiation. Plants need plenty of sunshine to power the photosynthesis process that in turn provides the energy that enables plants to grow healthily. Initially indoor farming will predominate on Mars and this will be in enclosed structures with minimal natural light. So, we can expect that in the early years there will be a dependence on artificial lighting (replicating the solar spectrum) to enable photosynthesis in plants. This will likely be powered by external photovoltaic panels (with integrated chemical battery systems to ensure reasonably long periods of light input).

Indoor farming of this sort will be resource-intensive – another way of saying “expensive”! – but it will nevertheless be a lot cheaper than importing food 140 million miles or more from Earth in Starships.

The amount of solar radiation at the surface of Mars is roughly 40% of the equivalent on Earth but because there is virtually no cloud cover, the amount of “insolation” (ie solar power available at the surface) is much more consistent. That sort of predictable solar power is really useful for farming on Mars.

Another plus point is that the seasons are much longer on Mars than on Earth (remembering a Mars year is almost the length of two Earth years) and – even better – spring and summer are also, proportionately, even longer (the seasons being less regular than on Earth). This means that there will be a longer growing season available. So, the outlook as regards insolation, is not so bad really. In any case, you could use reflectors such as mylar panels to reflect more solar radiation on to facilities similar to polytunnels (but adapted for Mars conditions), in order to ensure the crops are getting enough energy from the Sun. The fact that wind force on Mars is only a mere 5% of the equivalent on Earth means that it is much easier to make use of such reflectors without fixing them to large and expensive structures.

A reasonable temperature range. Prior to terraformation, you are not going to get a reasonable temperature range for growing crops on Mars unless you take the crops “indoors”, either within substantial structures or possibly inflatable and translucent polytunnel-type structures. The latter sort of farming habitats would be ideal because of course they could benefit from direct insolation (no need for photovoltaic panels).

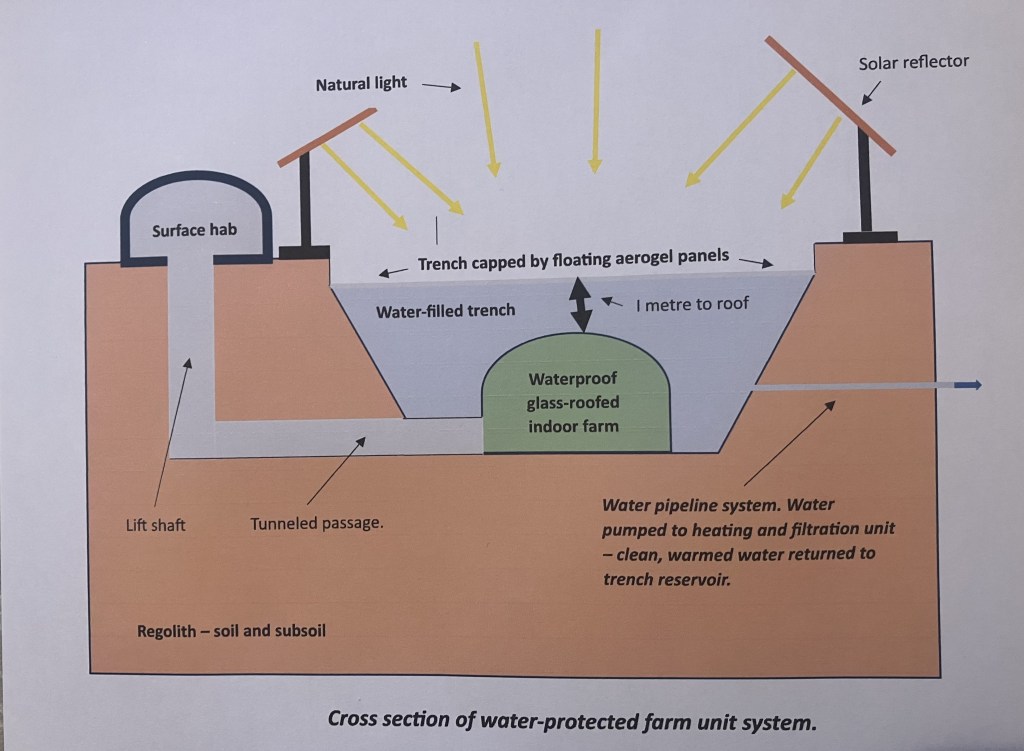

However, there is a balance to be struck here. We need to factor in the negative effects of cosmic and other radiation that can damage the health of plants (in the same sorts of way that it can damage human bodies). Surface radiation levels on Mars are about 17 times’ higher than on Earth. So, until terraformation begins to bring down radiation levels substantially (through the creation of a much thicker atmosphere for instance), we will need to protect our crops at the surface. No doubt various approaches will be trialled. We could for instance grow plants under thick transparent plastic domes. Or perhaps we could grow crops a metre or so under water, in clear plastic or glass panel structures (as in the following diagram).

Credit: Owen Louis David

One possibility that intrigues me is the idea we could use mirrors to direct sunlight on to crops. Mirrors reflect light but not gamma and other highly dangerous forms of radiation that can easily cause damage to plant cells. It might be quite complex setting up mirrors or reflectors to direct light on to plants, but no doubt the people of Mars would quickly become adept at this. As already mentioned, the weather is so benign on Mars (no storms, monsoons, hurricanes, or floods) that reflectors won’t require expensive frames and so on to keep them in place.

Ok, so we have a better idea about the sorts of things we need to do to make farming work on Mars. Now let’s look at how things might develop, reviewing the colony’s development in phases, beginning with the Early Missions.

Phase 1 – The Early Missions. It’s a reasonable assumption that Space X will be the first entity to put humans on Mars. Their Mission One is going to be huge – involving the landing of about 500 metric tons of supplies on the planet. With a crew of perhaps 10, the issue of how to keep people fed is not going to be that pressing. There will be plenty of cargo space for fresh food, chilled food, frozen food, canned food, dried food, and fermented food. In this phase, things such manufacturing the propellant for the return journey, performing maintenance work on the Starship rocket and identifying water and mineral sources will be much more of a priority than producing food.

Farming during this phase will be fairly basic – producing a range of salad crops under artificial lighting – a market gardening operation you might call it. The range of foods will expand during this period but farming will not yet be the priority yet that will become as the population reaches significant levels.

Phase 2 (from 10 to 50 years after landing) – A Planned Expansion. Long term, it’s obvious that Mars is going to have to produce its own food if it is going to become a self-sufficient colony. Phase 2 of farming on Mars will see a concerted effort to put in place the groundwork for this so that food imports are hugely reduced.

In this phase we are still likely to see indoor farming under artificial light prevailing. However, the facilities will be getting appreciably bigger. Agricultural facilities on Mars will likely resemble the large “vertical farms” that have been developed in recent years in major urban centres. Indoor farming of this type is very energy intensive, but that will not be an important cost factor at this stage on Mars. On Earth, urban vertical farms are competing with traditional open-air agriculture. Vertical farms save on pesticides, weather damage and transport costs but the very high energy costs currently limit the types of crops that can be grown indoors on Earth. Traditional agriculture of course largely gets its energy for free, directly from the Sun which is why farmers can produce food so cheaply. On Mars, where there will be no competing outdoors traditional agriculture to worry about, indoor farming will extend to a wide range of crops including arable crops such as wheat, barley and rice.

These facilities will be built so as to facilitate robot operations. Robots will use extensively to plant seeds, then tend and monitor plants as they grow. As on Earth robots will undertaking harvesting of crops – the main difference on Mars is that robot harvesting will be the norm. Mini robot drones may even be used for pollination in the absence of bees and other insects.

This period will also attempts to extended Controlled Environment Agriculture (CAE) to external structures that admit natural light – the equivalent of polytunnels on Mars.

Phase 3 (50 to 200 years after landing) – Mature CEA Farming – In this period we are likely to see a huge increase in natural light farming possibly with plastic domes, using concentrated Mars air. This will be partly a matter of necessity. A million person city relying on artificial light entirely would be a huge economic burden. One way or another I think we will see workable natural light systems developed, perhaps based on water protection and reflectors, to lower the negative impact of radiation.

Phase 4 (200 plus years) – Earth-like farming

Once Mars has been substantially terraformed (a huge undertaking that may spread over several centuries) we can expect to see farming on Mars increasingly coming to resemble farming on Earth. Eventually, there will be vast prairies north of the equator growing short-season wheat. However, Hellas Basin (in the southern hemisphere) may be the first location on Mars where we see Earth-scale agriculture being developed. The Basin is so deep that, with its atmospheric pressure being double the average on Mars, it will surely be the first region on the Red Planet capable of sustaining Earth-style agriculture. Here will sow the first wheat fields and, later, establish the first outdoor orchards. Probably the earliest we could expect to see this sort of scenario unfold would be after 200 years.

Post-terraformation crop agriculture will certainly resemble the equivalent on Earth. However, we may well see Mars agriculture diverge from the Earth experience in many ways.

What about dairy farming? Will we really see cattle with distended udders and all the suffering that goes with intensive animal farming? There may be an alternative. Scientists are already producing milk from bovine mammary stem cells. It seems to me that a Mars community is much more likely to be interested in developing that sort of technology than putting a lot of effort into cattle-raising, herd management and so on. The stem cell technology is still in its infancy but commercialisation is already in sight. A Singapore start-up called Turtle Tree Labs is well advanced with the technology and looking to begin developing markets. However, any new product will need to clear food safety regulations before it becomes available to the public. But in 20 or 30 years, by which time the issue of dairy farming might become relevant on Mars as the colony looks to develop milk production? Well by that point in time, it is very likely this technology will offer an alternative to the complexities of dairy animal farming and may well provide the best solution on Mars.

Of course milk from stem cells leads us on to the subject of alternatives to livestock farming for meat. The unappetisingly titled “lab meat” offers an alternative to rearing animals for meat. No descriptive name has yet won out. It’s also referred to as “cultured meat” or “clean meat”. Maybe “kind meat” would be a better label as the aim is to retain the fundamental characteristics of meat but without any cruelty to animals. My hunch is we could well see a reluctance among the people of Mars to recreate the factory farming and intensive meat industry we see on Earth. It would be a different type of factory farming with meat being produced in purpose-built factory facilities., with pharmaceutical standards of cleanliness.

While I am suggesting livestock farming might never get a hold on Mars, I do see it as a possibility that we might see a return to hunting as a form of meat production. So, on this approach animals would live in the wild but a certain number would be culled each season. Such culling of bovine and other animals is already a key feature of parks management on Earth. Were this approach to be adopted, hunting would be highly automated I think (rather than involving humans getting up close and using firearms). We could expect to see drones approaching herds and taking out an animal with a very accurate single shot. Of course, we can’t tell how a Mars community is going to view the issue of meat production and animal rights. However, it is certainly the case that in natural environments, most animals (especially the type we eat) are predated upon and, so, I think a fairly strong ethical argument can be made for continued meat-eating (for those who want it) on the basis of culling.

Well I hope you have found this introduction to farming on Mars useful. Let us know what you think about these issues. What would be your recommendations? Being able to farm on Mars successfully is probably the most important challenge we face in trying to establish a human colony there.

Leave a comment